The Lyvennet rises on Crosby Ravensworth moor, passes Crosby Ravensworth, Mauds Meaburn and Kings Meaburn, joining the Eden at Temple Sowerby.

Perhaps the name of Lyvennet comes from the “Llwyfenydd”, referred to by the Welsh bard Taliesin. However, the majority of local place names are Norse, reflecting the influx of settlers from Norway, via Ireland, 1,000 years ago.

The village of Reagill was the home of John Salkeld Bland who, about 1860, composed a manuscript entitled 'The Vale of Lyvennet, its picturesque peeps and legendary lore'.

This is a remarkable book, now published as a facsimile of the original printed version of 1910 by Titus Wilson of Kendal (then printers of The Westmorland Gazette).

Immense care has been expended on this book and a finer job could not have been done.

His accounts of manorial disputes were derived from ancient parchments of his great uncle, Mr Salkeld, and interpreting these ancient documents must have been a major task.

Educated locally, he visited America, unusual for those days.

In the summer of 1866 he made a study in water colours of over 100 wild flowers, executed with meticulous skill.

In addition to botany, he also studied geology and chemistry.

Before he was 22, he had made a geological map of the district (there were coal mines at Reagill in those days), which was presented at the Manchester Geological Society at a meeting on December 30, 1862, with a paper entitled: 'On the Carboniferous Rocks in the neighbourhood of Shap and Crosby Ravensworth'.

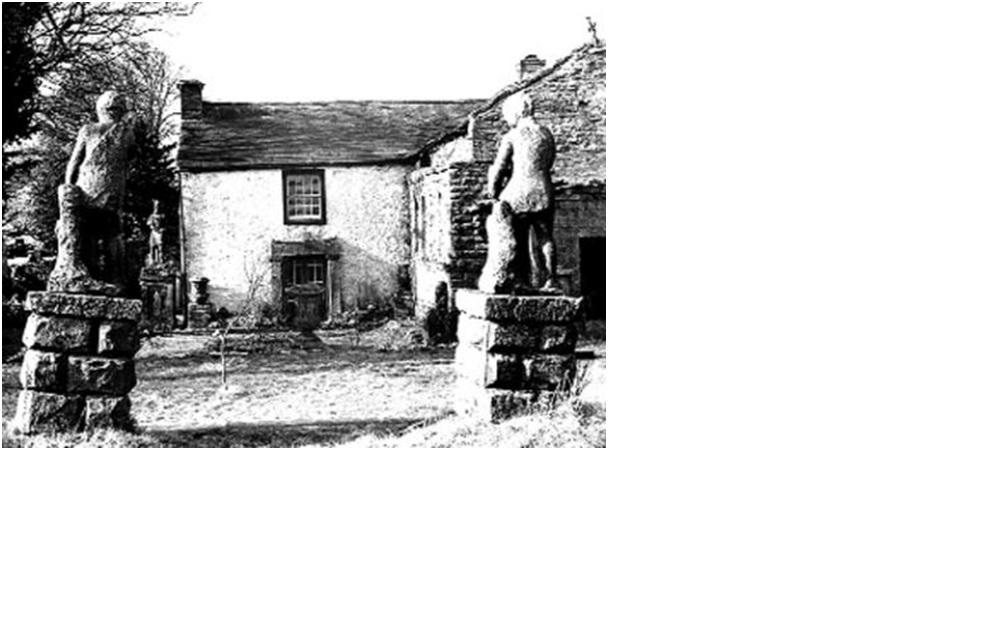

Another remarkable man was his uncle, Thomas Bland, famous for his garden at Reagill.

This garden was filled with statues and paintings displayed in stone alcoves, all his own work.

Other sculptures included the stone set up to commemorate Charles II’s halt at the head of the Lyvennet and the statue of Britannia, erected, at his own expense, to commemorate the accession of Queen Victoria at the Shap Wells Hotel.

Thomas Bland also commemorated this event by holding an annual party in his gardens on the Friday nearest the event.

A band of music was engaged and there were lavish decorations, lectures, addresses, dancing and 'other recreations'. Up to 1,400 people might be present.

The scale of the statuary was overwhelming and many speculated how one man could achieve so much. It was a labour of love.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here