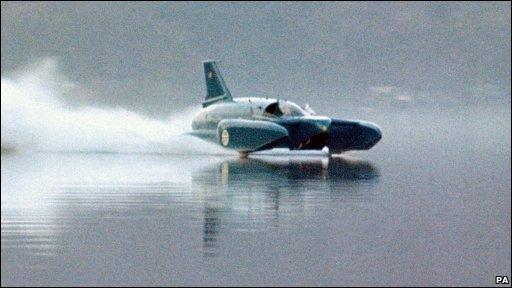

A painstaking mission to bring Donald Campbell’s iconic Bluebird K7 back to life is beginning to take shape – but no deadline has been set. TOM MURPHY reports.

BLUEBIRD K7 is considered a national treasure. It holds a special place in the hearts of many people who remember the determination of one man who paid the ultimate price for pushing himself and engineering boundaries to the limit.

Restoring it using as much of its original parts to thunder down Coniston Water once again was never going to be an overnight job.

"You can go to Virgin Galactic who have £400m to spend on a global project and ask them when they are going to be done and they couldn't tell you anymore than we can," Bill Smith, who is leading the project, explains from his workshop in North Shields on Tyneside.

"There could never be a deadline. There are still lots of things we don't understand. We are in unknown territory. It will be done when it's done and nothing on this Earth will induce us to hurry up."

Donald Campbell CBE was killed instantly on January 4, 1967 in a spectacular crash as he was attempting to beat his own 285mph water speed record on Coniston.

The wrecked Bluebird was lost for 34 years before being recovered along with Mr Campbell's remains at the bottom of the lake by Mr Smith in 2001.

Since then, with Mr Campbell's daughter Gina's blessing, a dedicated team of volunteers have set about restoring it to its former glory.

"There are 20 people working in the workshop," said Mr Smith. "The furthest regular visitor is from Somerset, there are a few from Cumbria, one or two from Teesside, Liverpool and Cheshire. They just come along when they have a Saturday free and can come do some work."

Using 90 per cent of the craft's original parts and fabric, the project, as expected, has proved challenging.

"We have just started building the sponson tops," said Mr Smith. "They are half new and half original so it's a bit of a case of matching up the old with the new and getting the worst of the lumps and bumps out of it.

"It's never been tried before. People have made new panels but trying to resurrect old ones and make them into new ones while making sure it flows nicely has been a bit of a challenge.

"Of what came out of the lake and what was available to us you can put the bits we haven't used in a couple of shoe boxes."

The Lake District National Park Authority has already given permission for proving trials to exceed the speed limit on Coniston Water and Mr Smith hopes when it is complete people will visit in their droves to watch the craft return home.

"The ultimate aim is to show the machine to all the people who missed it first time round," he said. "There are a lot of machines lying in museums gathering dust and you will never see one operated.

"They are dead. Museum people are a strange lot who like these things to remain dead. The idea of lighting a fire in it and making its wheels turn or its wings flex terrifies the life out of them.

"I hope a lot of people would come see it. It is not what it is about from our point of view though. We are doing it because it's a piece of engineering and we enjoy putting it together and learning from it to have that knowledge in a form we can pass on.

"It is not about attracting lots of people to come see it - that's just a by-product of it - but if Coniston and Cumbria can benefit from that then that's great."

After the trials, the craft will go on permanent display in the new purpose-built Campbell Wing of The Ruskin Museum - but that won't be the end of its life.

"It will have to come out a few times a year," said Mr Smith. "If you leave machines lying around they tend to seize up and stop working so we will have to put in place a maintenance programme and trundle it out now and again.

"What you will be looking at is not some dead husk of a junk - it will be a living breathing machine which is something you don't often see in museums."

Visit www.bluebirdproject.com to follow the project.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here