In the second of his series, Will Garnett reveals the link between Grange-over-Sands and the Plimsoll line, that has saved many sailors’ lives over the years

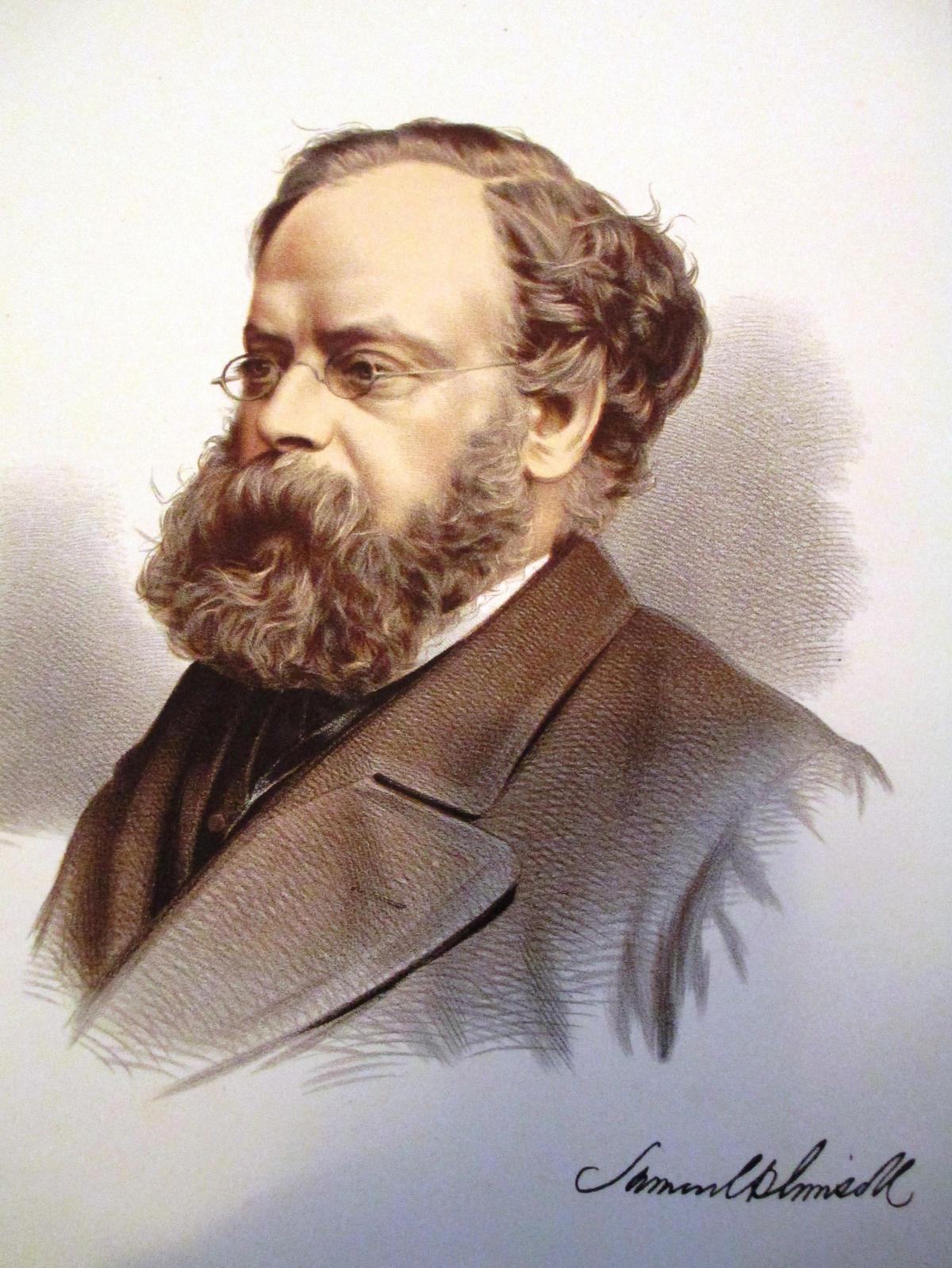

Plimsoll got himself elected an MP and set about trying to find a way to convince people that many ships were not seaworthy when they left port.

He used every opportunity to harangue MPs whom he considered to be opponents of reform. At the same time, he needed to change the public perception of merchant seamen, to show that the seamen were genuinely hard-working men.

He also set about providing evidence to prove sailors' complaints of lack of seaworthiness of many vessels were valid.

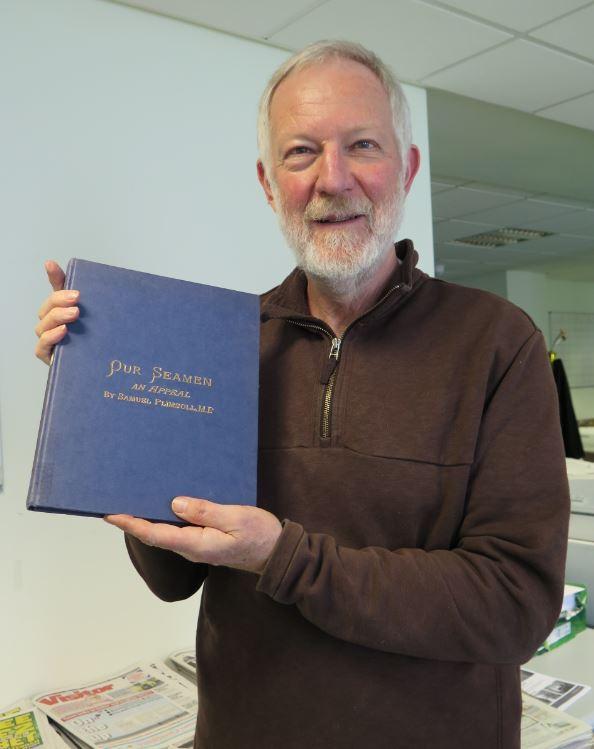

In his year in Grange-over-Sands in 1872, Samuel managed to bring all these disparate statistics together into one immensely powerful volume.

He used Board of Trade statistics to show that many ships went down close to the coast, often in ‘very fine weather’. Between 1861 and 1870 5,286 ships had gone down – with the loss of 8,105 lives.

The statistics were overwhelming. The public were already aware of the Bridlington disaster that had been widely reported: overladen coal-carriers went down close to the shore in easy sight of the people of the town – who also had to watch their own lifeboat crew founder in a vain attempt to rescue stricken passengers on the ships.

It is one of the features of Plimsoll’s campaign that both Samuel and his wife were equal partners in the campaign. Even though the national newspapers in male-dominated Victorian England gave all the praise to Plimsoll, without his wife Liza and her female supporters the campaign could not have succeeded.

They worked tirelessly but in the background, ensuring that male supporters like Lord Shaftesbury had the ammunition to take the fight to the country. Significantly, Florence Nightingale donated £5 to campaign funds, thereby endorsing the positive image of merchant seamen, and reinforcing the national importance of the Plimsolls’ campaign.

Financial support for the campaign came partly from individuals from every walk of society; and, crucially, from workers becoming increasingly unionised in the second half of the 19th century. The coal mined in Durham and Yorkshire was taken by ship to the London market, and the miners well knew the dangers their comrades faced on the sea. Each miner in the NE coalfields donated one shilling, and this enabled two cheques of £1,000 to be sent from the Durham and from the Yorkshire miners to the Plimsolls.

Plimsoll’s Grange-written treatise provided the essential focus for the whole campaign. It identified irrefutable evidence of the need for change, together with ammunition to counter the arguments of the rogue shipowners.

And it presented both shipowners and crew with a simple, easy to administer solution that would enable all parties to establish instantly whether or not a ship was overloaded and therefore not seaworthy – the aptly named Plimsoll Line. Samuel Plimsoll and his wife had raised sea safety to the national conscience. Samuel could not have done this without retiring to Grange-over-Sands to collect his thoughts, to assemble his evidence, to write the book that moved a nation.

Grange-over-Sands can be justifiably proud of its (not yet) famous son!

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here