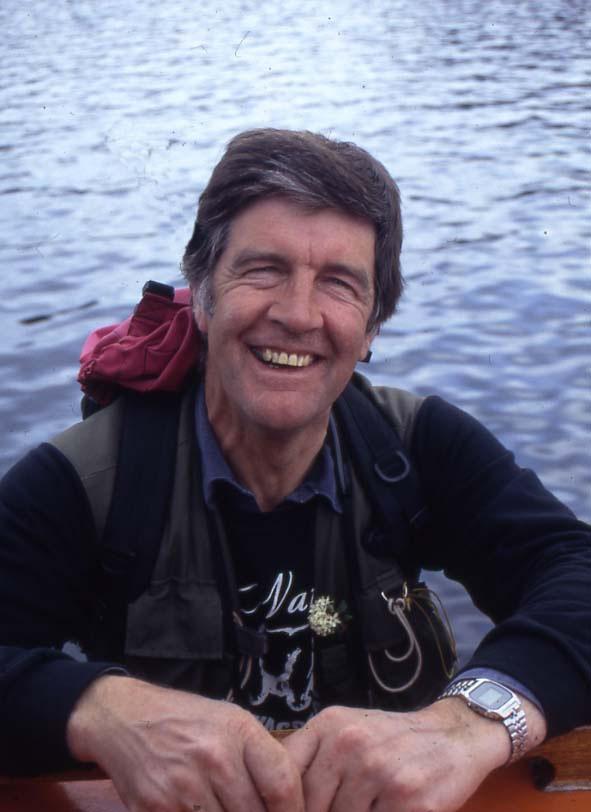

Following the recent reports of Lakes adventurer Paul Rose coming face to face with an 800lb polar bear on Baffin Island, Dr Kent Brooks, of Kendal, a retired doctor and Reader at the University of Copenhagen, recalls two incidents when he also had close encounters with bears, in 1982 and 1995.

Dr Brooks, who is also an Emeritus Professor at the Natural History Museum, believes he might be the only scientist to have been both wounded and to have shot a bear.

In 1982 I was working for the Northern Mining Company, prospecting for gold and other metals. Myself and my assistant, Bjørn Thomassen, had been flown in by helicopter to Ryberg Fjord, a remote location in East Greenland. This is about 400 km from the nearest inhabited location.

One morning in my tent at about 4am (it was summer and light for 24 hours) I became aware of an immense weight on my legs and I suspected some kind of prank by my assistant.

However, as I struggled to withdraw my legs, I was struck a blow in the side and became aware of a strong, unmistakably animal smell. I was now aware I was dealing with a bear and took my loaded calibre 45 pistol from under my pillow and, lying on my belly, cautiously opened the zip door of the tent, only to be confronted by a bear’s face only a foot or so away.

Uncertain whether a shot would kill the bear before it could kill me I hesitated and shouted “Bjørn, bjørn!”, this being the name of a bear in Danish. My assistant, whose name was also Bjørn, interpreted this as a call to wake up and a sleepy voice was heard protesting the early hour. In order to dispel confusion, I now shouted “Nanok, nanok!” – the Inuit word for bear.

This seemed to scare the animal, which began a leisurely retreat, glancing back all the time. Seeking to expedite matters, I fired a shot into the ground by the bear’s feet, but this had the undesirable effect of making it turn around and it showed all signs of returning, although it thought the better of it and ambled off round a rocky outcrop.

At this point, Bjørn appeared from his tent with a camera, saying “Where is it?” He was quite annoyed at not getting a snapshot.

We climbed the rocky outcrop and were amazed to find the bear was now a tiny speck disappearing into the distance.

My tent was badly ripped and I had a large bruise on my side but, all in all, we had got off lightly!

In 1995 we were camped in a remote location, at about 8,000 feet in the Prince of Wales Mountains, about 100 kilometres inland from Skaergaard, which lies about halfway between Ammassalik and Scoesbysund, the only settlements on the east coast of Greenland.

I was doing scientific work related to the origin of the North Atlantic Ocean for the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland.

These mountains are nunataks, protruding from the Inland Ice (the Greenlandic ice-cap). Due to their remote location, far inland, we had not thought it necessary to take firearms although my companion Phil Neuhoff, a farmer’s son from Iowa, usually equipped himself with an impressive array of artillery. However, just as the helicopter was leaving the base camp I had gone back to pick up something, noticed my pistol (a Husqvarna 9 mm with three rounds in the magazine) and took it anyway.

At this time, a booklet was circulated to geologists to guard against bear attack and it was recommended to surround the camp with a trip wire. It was further recommended that the tins of chilli con carne in the rations box made an excellent bait.

Some evenings later, Phil and I were outside stirring a pot of chilli con carne on the primus and contemplating the vast expanse of ice extending to the horizon, when Phil said: “Hello, we’ve got company”.

I looked round to see a bear not far off. Rapidly retrieving the pistol from the tent, I fired a shot into the ground just in front of the animal, which was now about 15 yards away. This only had the effect of interesting the bear, which continued approaching, perhaps with greater alacrity.

There seemed to be only one thing to do and that was shoot. As might be imagined, I had a slight tremble and the shot was not lethal, but appeared to break the front leg of the animal, instead of entering the chest as intended.

One reads there’s only one thing more dangerous than a polar bear encounter and that’s an encounter with a wounded bear.

Fortunately the animal backed off and made for the nearby glacier, trailing the wounded leg and leaving a trail of blood.

Up on the glacier, it lay down on the ice and was still for at least 10 minutes. I suggested I should go up and see if it were still alive and, if not, finish it off. Phil, however, advised against this course of action, pointing out I now had only one round in the weapon.

With some difficulty we called up base and the helicopter was sent out, arriving after about an hour. As soon as the engine noise was heard the bear showed its first signs of life and when the aircraft was overhead it stood up and began to run with amazing speed. I thought: “Good thing I did not approach it, thinking it dead."

It was soon finished off and it proved to be a young animal. The pilot said “You’ve killed a baby”. Nevertheless, four men, one on each leg, were unable to lift the carcass into the helicopter and it had to be carried in a net sling.

I was unhappy about this incident. Not only did I not want to kill a polar bear, but doing so has consequences. I had to report in detail the incident to the authorities and I was later much relieved to hear that my explanation was accepted - some people who have killed bears have been criminally prosecuted. Finally was the question of the carcass. The law states this must be delivered within a reasonable time to the local police. In this case that would mean an 800-kilometre round trip, costing a small fortune. However, in view of the circumstances, we were given permission to only deliver the skin, meaning we could eat the meat ourselves.

Confronting a wild and dangerous animal in nature is an alarming experience for most people and is difficult to visualise until experienced. For this reason I do not take seriously the many people who questioned my decision to shoot on this occasion.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here