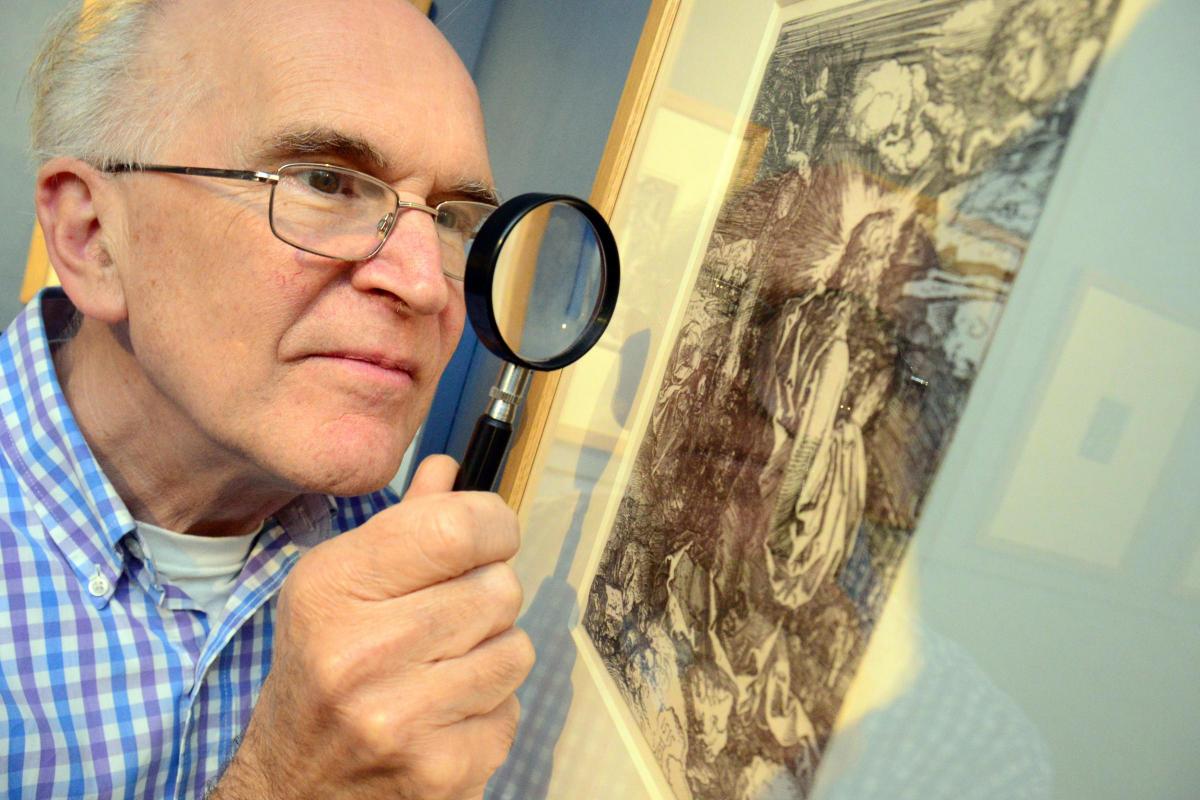

ALBRECHT Durer: Beyond the Burden of Brilliance puts the work of one of the finest exponents of Northern European Renaissance art firmly on the hallowed walls of Brantwood's Blue Gallery.

Running at the former Coniston home of John Ruskin until October, the exhibition celebrates the finely crafted woodcuts and engravings of the versatile Nuremberg-born artist (1471-1528), regarded as a brilliant painter, draftsman, and writer, though his first, and probably greatest artistic impact, was in the medium of printmaking.

Technically, the German's prints were exemplary for their detail and precision. Trained as a metalworker at a young age, he applied the same meticulous, exacting methods required in this delicate work to his woodcuts and engravings, notably the Four Horsemen of his Apocalypse series (1498), and his Knight, Death and Devil (1513).

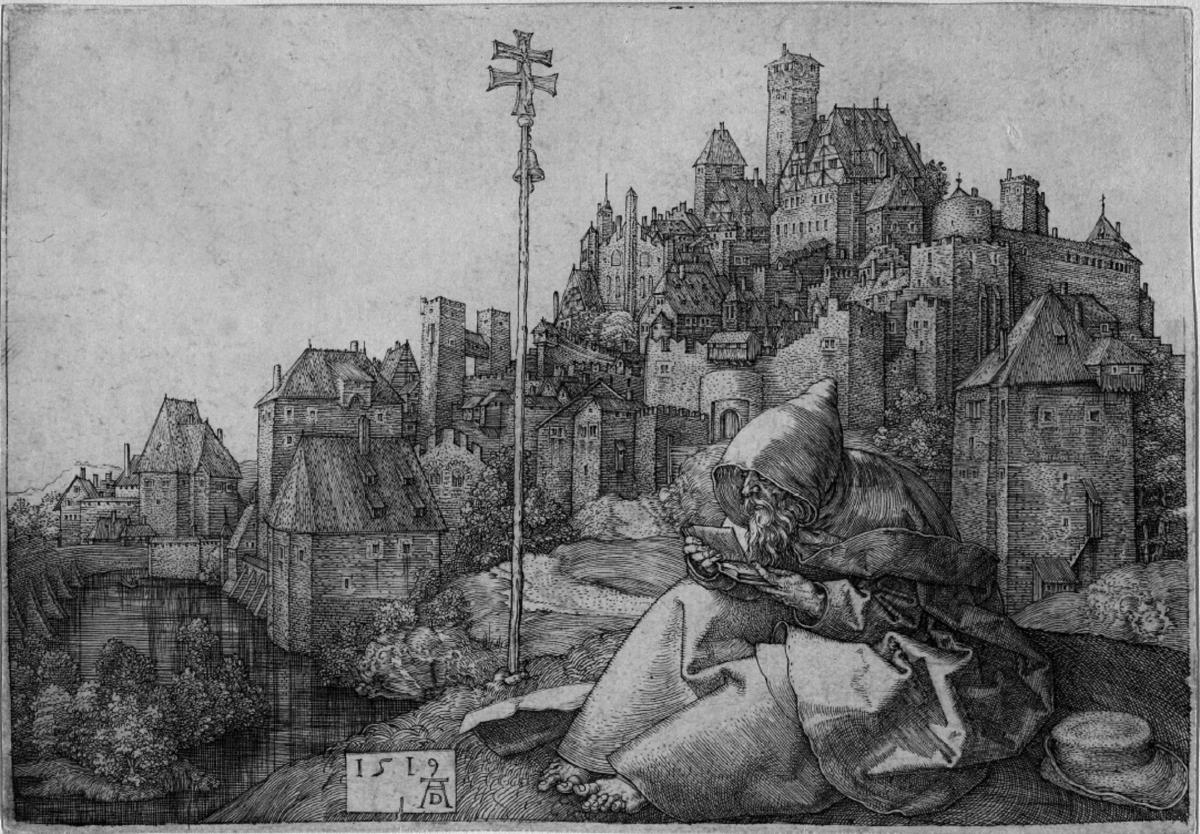

St Anthony the Hermit 1519 is one of the very few prints that Durer created in landscape format, and where he employs the full range of skills that he mastered during 20 years as an engraver.

Albrecht Dürer was also a great admirer of Leonardo da Vinci. He was intrigued by the Italian master's studies of the human figure, and after 1506 applied and adapted Leonardo's proportions to his own figures. In the 1520s, Leonardo illustrated and wrote theoretical treatises instructing artists in perspective and proportion. Northern European artists were well impressed with the results, none more than the gifted Albrecht who even went to the trouble of writing The Arts of Measurement (1525) and On Human Proportion (1528). However, to be fair, long before this, northern European artists had achieved considerable success in producing naturalistic depictions of the human form.

Apparently, Durer was an artist upon whom Ruskin lavished praise and criticism in equal measure. In a cycle of 14 of Durer’s finest sacred engravings and woodcuts from Manchester’s Whitworth Art Gallery, Brantwood explores the artist’s struggle to balance faith and fortune, virtuosity and virtue.

Brantwood director Howard Hull, whose curated the exhibition, says that in many ways Ruskin's problems with Durer were akin to his more public disagreement with Whistler, who famously sued Ruskin for slander.

"In both cases there is a sense in which the artists displayed characteristics which Ruskin had sublimated or wished to sublimate in himself," explained Howard. "To many of his critics, Ruskin’s writings were every bit as egotistical and flamboyant as Durer. Like Durer, this was borne out of a powerful combination of precociousness and virtuosity on the one side and a deep thinking, sensitive and devout nature on the other."

"It's interesting to note that Ruskin, like Durer, was the victim of an unhappy and arranged marriage which was childless. In later years Ruskin, like Durer, in the centre of celebrity, also became a lonely figure. Ruskin and Durer alike are capable of crystalline objectivity of vision when studying from nature, yet both seek comfort from the mysteries of existence in the formal systems of science and art. Durer, like Ruskin, carried with him a profound sense of social duty and believed that art was a moral force. But both moved in dream-like and visionary spheres, increasingly haunted by personal demons.

"For all that he might criticise him, Durer offered Ruskin a model of talent and artistic energy when it came to using his work as a teaching aid."

Arranged chronologically in the years between 1498-1523, Brantwood’s exhibition showcases some of Durer’s most important but today least celebrated works. It explores how Durer developed his use of print as he sought to define his approach to the sacred at a time of religious and secular change. Today’s admiration for Durer is based largely on the popularity of his remarkable studies from nature and his famous self-portraits. However, a large amount of Durer’s public work was religious in nature and the Brantwood show traces Durer’s struggle to channel his artistic virtuosity beyond his desire for fame in order to resolve the intellectual and spiritual journey of his faith.

The majority of works in the exhibition are on loan from the Whitworth with supporting material from Stonyhurst College and a number of private collectors.

To tie-in with the exhibition, Howard will give a talk on Albrecht Durer in Brantwood's Coach House Loft on Saturday, July 16.

Elsewhere at Brantwood, Heysham-based artist Patricia Haskey's A Feeling for Landscape is on show in the Severn Studio until August 7.

Sketches, oil paintings and mixed media paintings, using watercolour, gouache and soft pastel, feature in Patricia's exhibition, which is about being emotionally present in the landscape of Ruskin’s beloved Lake District.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here