Historian Roger Bingham, of Ackenthwaite, describes the immediate aftermath in the Westmorland area of the declaration of war.

'Goodbye Piccadilly, farewell Leicester Square, it’s a long way to Tipperary”, sang Westmorland Territorial Army soldiers as they were marching off to war, though few had previously heard of the places in their pop song, let alone visited them.

Most had just hurriedly returned from a TA training camp at Carnarvon. Hardly any had been further away than Morecambe or Blackpool.

Perhaps, too, they were equally oblivious about the fate of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand, whose slaughter at Sarajevo on June, 28 had, somehow started it all.

Yet by August, 8, only four days after the declaration of War, they paraded, excitedly, towards Kendal railway station, off to deliver ‘gallant little Belgium’ from the forces of the German Kaiser.

On New Road the TA commander Major Argles (who did not, himself, go to war) was ‘drawn up in his motor car to take the salute’.

Here The Westmorland Gazette reported: ‘boys grabbed dad’s kit bag and shouldered it and dad kept his teeth closed and marched on resolutely while an old grey haired man fell in beside his son.’

In Stramongate the cheering crowds drowned out the town band, but on the station platform, where virtually all the local ‘gentry, the corporation and magistrates were assembled’, the tumult was silenced when the Mayor assured the men ‘that their dependants would be well looked after and pensions from 10 shillings to 17 shillings a week would be given for loss of a limb’.

He said nothing about the loss of life. In any case no one envisaged that four years later the names of 316 of Kendal’s cloggers, clerks, grammar boys, mill hands, farm lads and K shoes clickers would be inscribed on the town’s 1914-18 War Memorial. Nor that a proportionate cull would be commemorated in almost every other place.

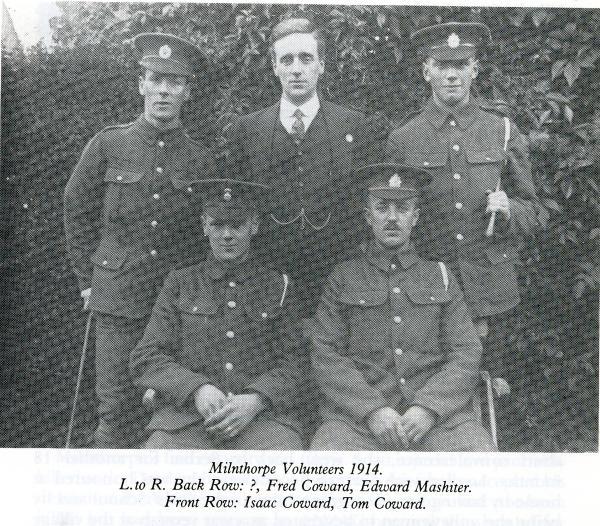

Meanwhile, at Milnthorpe Station, 3,000 men and 27 horses, having vacated TA camps at Farleton and Kirkby Lonsdale, entrained for the front. The next day seven Milnthorpe reservists were given ‘a hearty send off’.

There was less enthusiasm at Milnthorpe’s first recruitment meeting but when women joined the fray, a ‘Wake up Milnthorpe’ meeting was a total success.

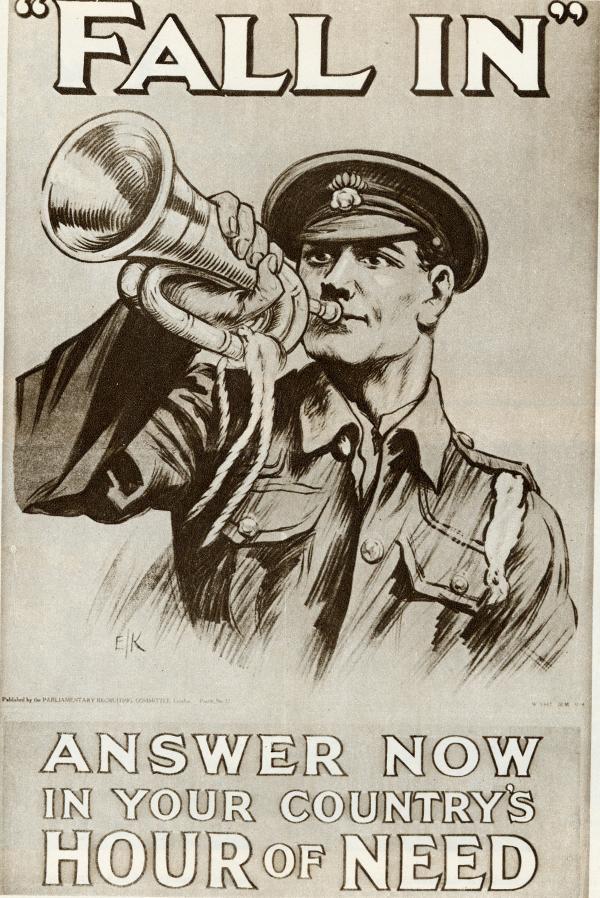

Standing under the famous poster of the War Minister Lord Kitchener asserting ‘Your King and Country need YOU’, Lady Bagot of Levens Hall threatened that if a lad pleaded ‘mother won’t let me go’, then the mother’s name should be furnished so she could ‘go and see her’

. Another Amazon, the wife of Colonel North of Old Hall, Endmoor, announced that if any of her 17 relations serving in the forces did not come back ‘she would not wear mourning but a white band in honour of gallant men who gavetheir lives to shield women and children’.

Immediately, 30 men came forward, including a posse of village sportsmen who, calling themselves ‘the Milnthorpe Athletic Volunteer force’, formed a ‘Pals Battalion’.

Though this meant that they could serve together, time eventually showed that they might also be killed together.

Soon they were photographed drilling with broom sticks and six weeks later they were off to take on the fully-trained conscripted forces of the German Empire. Elsewhere, girls were ‘enjoined to tell their boyfriends to go away with you and fight for your country’s sake, I’d rather have you than a German’.

Speeding things up the MP, Colonel Weston, believing ‘it will all be over by Christmas’ warned young men to ‘hurry up before it’s too late. If you hold back you’ll be ashamed in three month’s time’.

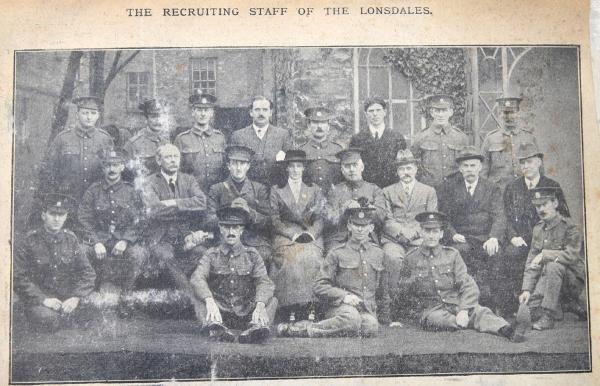

Despite wartime demands, the Colonel recruited men from his Gunpowder Works at Gatebeck. Similary, K shoe workers joined up as as the Kendal factory received War Office orders for 400 army boots. By October, there were over 1,000 Kendal Pals. But, with only half of Kendal’s population, Ulverston’s roll call of 741 was even better.

Other impressive figures included Ambleside with 75 recruits, Appleby 49, Grange 54, Grasmere 30, Kirkby Lonsdale 52 and Windermere 161. Apart from Endmoor, where Colonel Weston signed up 49 men, Holme with 30 recruits from a population of 750 raised the highest proportion of village men.

Yet, as the ranks swelled, public enthusiasm dwindled.

There was no mayoral party, and ‘little swagger and few strains of Tipperary’ when the trains steamed away in September. In contrast, when a train load of Belgian refugees arrived, ‘ the crowd grew elated’.

With them came atrocity stories. Drummer boy Snaith, from Kendal, had seen ‘German Uhlands spearing wounded British Soldiers; then it was every man for himself: God knows how I got away so fast’.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article