Historian Roger Bingham of Ackenthwaite, describes life on the home front during the First World War

WAR broke out bang in the middle of the holiday season.

On August Bank Holiday Monday, 24 hours before hostilities began, it was reported that packed excursion trains, apparently unimpeded by troop movements, had provided Windermere with its greatest ever ‘invasion’ - of holiday makers.

Soon the uproarious departure of the first troops, which at Coniston were led by a rag time band from a holiday camp, added to the carnival atmosphere.

Initially, it was business as usual and a Westmorland Gazette advertisement cheekily announced that all Blackpool’s hotels remained open.

Grasmere Sports went ahead but the County Show was cancelled to provide more time for farmers to fill the gaps left by reduced food imports.

Elsewhere much of normal life went on as usual.

Down at Silverdale the big news was the gathering of ‘two fine mushroons’ measuring 18 inches and 15 inches round.

Initially private building was not halted as is indicated by 1915 datestones on large villas built at Heversham.

Judging from Westmorland Gazette advertisements, interest continued in the latest dress fashions, which saw hem lines of ladies’ dresses rise an inch a year from ankle length in 1914 to mid calf in 1918.

At the autumn fat stock sales a shorthorn bull sold for 950 guineas, thrice its pre-war value.

Such profits, or profiteering, contributed to a 400 per cent increase in agricultural incomes during the war.

Although there were acute shortages at the height of the U-boat campaign in 1916, food was never the obsession it became during and after the Second World War when rationing lasted from 1940-1954.

Panic buying, at first, led to price rises. Sugar went up from 2d to 3d a pound and flour from 1s 8d to 2s 3d a stone.

To replace imported wheat, a loaf made from barley and rice was proposed although, as Westmorland had no paddy fields, the rice would have required shipping space.

Other hardships included two meatless days per week, for which the Ministry of Food proffered such gastronomic alternatives as haricot and tapioca pie and carrot croquettes.

A ‘grow your own vegetables’ campaign failed when only 12 people turned up to a meeting addressed by Kendal’s noted horticulturist Clarence Webb.

Recruitment of land girls was more successful, although their pay of 15 shillings per week was stingy compared to the male farm labourer’s wage of 38 shillings.

Moreover, they had to provide ‘a uniform dress for wet and fair weather and strong shoes with wooden soles - costing 4s 6d’.

The K Shoes girls who made them got £2; but this was meagre compared to the earnings of Barrow’s 16,000 women munitions operatives (many of whom were drawn from South Lakeland), who could afford ‘in no time at all to deck themselves out in £10 fur coats’.

A female labour force had come into being at the very start of the war when 14 Kendal Post Office clerks, who had formed a Pals Battalion, were instantly replaced by women; down at Burton Miss Bainbridge became one of the first ‘post ladies’.

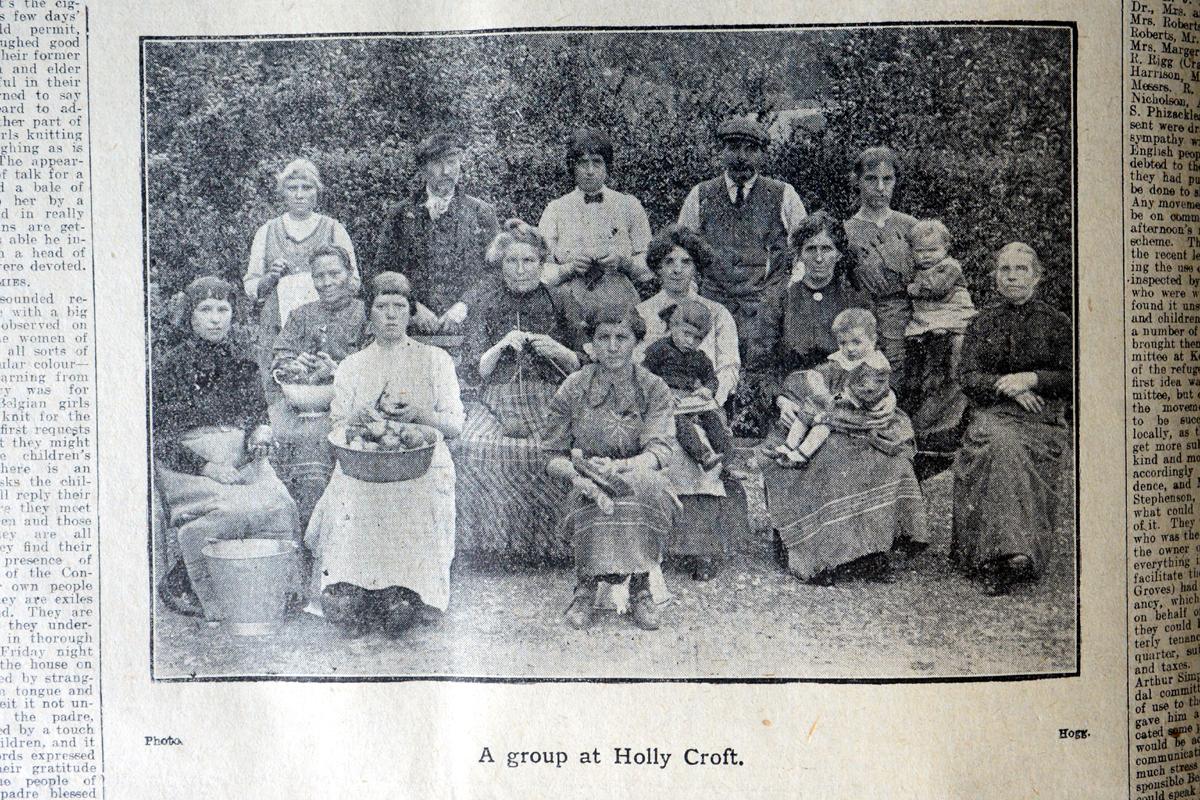

Although mail increased enormously, twice daily collections and deliveries continued and, it was claimed, that The Westmorland Gazette, along with ‘soldiers comforts’ provided by innumerable women’s working parties, reached France within 48 hours.

At Christmas thousands of parcels were despatched to the front. Most contained knitted garments, cocoa, biscuits, candles, vaseline and (permanently boosting tobacco addiction) cigarettes.

In 1915, Private Herd asserted he had eaten, in the trenches, tinned peaches sent by well wishers. In return he and other Pals sent home such ‘souvenirs as German watches, field glasses, jagged bayonets and even cameras’.

But they had refused offers of prayer books held out by surrendering ‘Huns’.

Locally, there was no anti-German ‘Hunbashing’ because there were no ‘Huns’ to bash.

No one objected when a profile of a Border Regiment Colonel revealed that he was married to a Princess with a German title - but so too was the King!

Scores of German tourists were officially helped to slip away to east coast ports, from whence they reached their Fatherland via neutral Holland.

But three German residents were fined 25s at Ambleside for failing to register as enemy aliens and an Austrian waiter, who claimed he had not known that his country was at war, was interned.

To be on the safe side, however, Mr Voght, a Kendal Chemist, found it necessary to explain that, despite his German sounding name, he was British.

Similarly, Wilkinson’s Organ works advertised that their Weber pianos were ‘Made in England’.

Nevertheless, fears of spies and saboteurs abounded. When Shepherd’s Tool works in Kendal burnt down the crowd suspected sabotage as the firm was manufacturing trench pickaxes.

Briefly, an armed guard was placed on Arnside viaduct until it was deemed that the platoon was more urgently required at the Battle of the Marne than in the Kent estuary.

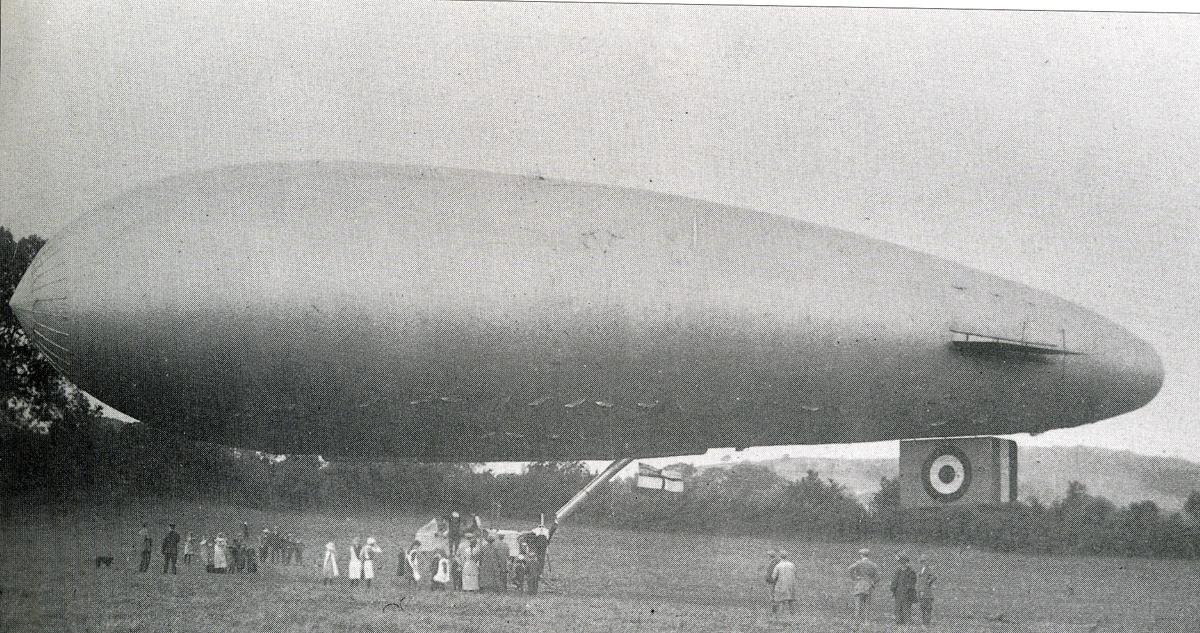

But, excitingly, an airship did float over Morecambe Bay and, in 1915, a Royal Flying Corps balloon landed at Moss End, Preston Patrick.

After German Zeppelins reached Lancashire in 1916, night-time lighting restrictions came in. Along with other offenders, Mr Brennan, a Kendal pork butcher, was fined £5 after a light from his open shop door had been observed by the Chief Constable.

Some of war’s horrors were revealed by patients who were cared for in temporary military hospitals at Kendal, Grange, Ulverston, Windermere and elsewhere.

At the height of the Gallipoli campaign in 1915, Kendal’s Women’s Voluntary Aid Detachment hospital based at The Friend’s School in Stramongate, unloaded 100 wounded at dead of night, in 40 minutes.

Between 1914-18 Kendal’s VADs cared for 1,822 patients, only two of whom died!

All 80 nurses were unpaid and the bed linen was washed free of charge by washer women from the municipal wash house.

Less worthy females included three teenagers who were fined for attacking Military Policemen who had been trying to arrest a drunken soldier.

For girls who had fallen ‘victims to the cruel selfishness of men’, St Monica’s Home for un-married mothers opened in Kendal.

As an alternative to ‘cruel selfishness’ a Union Jack Social club for servicemen was set up from where, ‘cost price garments ready to be made up’ were available for their children.

Among older children, however, an increase in delinquency, attributed to ‘absent fathers’, led to Kendal’s Juvenile Library being closed because ‘on some occasions the children had converted it into a urinal or common closet’.

What had the world come to?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article