A fascinating Great War war diary gives Katie Dickinson an insight into both the horror and tedium of life in the trenches

GORDON Audland’s diary, which reveals life in the trenches between 1915 and 1919, is deemed such an important World War One document, the original is now kept in the Imperial War Museum.

Born at Wellingborough in 1896, Gordon was initially expected to follow his father’s footsteps and become a doctor, but the war intervened.

He volunteered at the earliest opportunity and on his 18th birthday – December 20, 1914 – was given a temporary commission in the Royal Artillery Reserve.

His diary begins at the start of his service in France in April, 1915, and ends in June, 1919, when he reliquished command of the 16th Battery RFA, which he commanded from the summer of 1917.

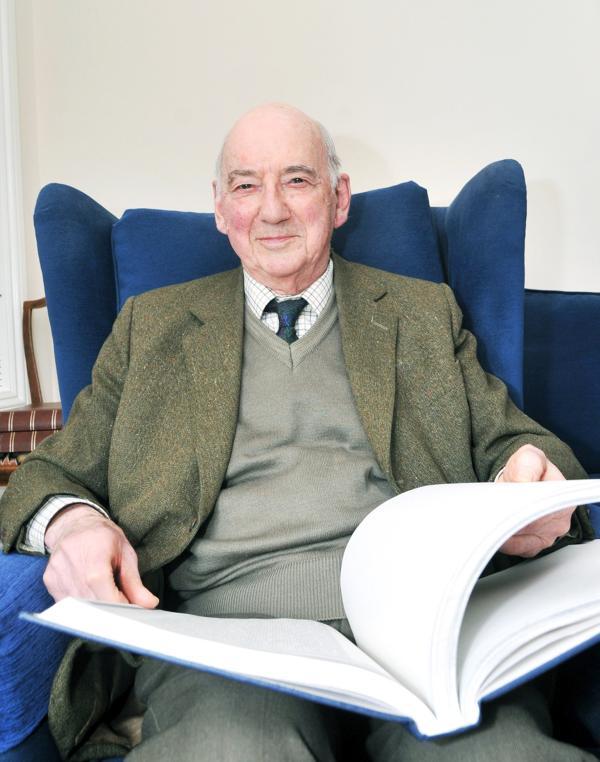

Gordon’s son Sir Christopher Audland, who like his father has now retired to the family home in Ackenthwaite, described him as ‘a meticulous note-taker’.

This is certainly borne out by his diary, which for virtually every day during his time in the trenches was kept up to date with his activities, whether that was shooting, marching, rat-catching or reading.

The first passage which captures in detail the horrors of the fighting comes on May 9, 1914 , when Gordon wrote: “During the morning the wounded began to come back and there was one continuous stream along the road past the battery.

“Some walked along alright, others helped along by their less seriously injured friends, many on stretchers carried by the RAMC bearers who must have had a frightfully hard time of it.

“It is ghastly to see some of them drenched in blood and yet walking or hobbling back.

“I should think that during the day from two to three thousand wounded came back by that road alone, and there were a great many who could not be brought in.

“Some on the stretchers were a ghastly sight; one man I saw had had the lower part of his face blown away but some who were hit through the lungs were the worst.”

During the war he divided his time between the gun position and observation post, which would have been in or near the front line.

He participated in the major battles of Loos, Vimy Ridge, the Somme, Passchendaele, Cambria, and the final advance into Germany – and in terms of physical injury emerged with only three splinter wounds.

But the experience took its toll in other ways. “Nobody who has not been in this fighting can possibly imagine how awful it is,” Gordon recorded on July 28, 1916.

The trauma of seeing fellow soldiers dead and wounded on a daily basis is referred to numerous times.

“They found the remains of two of the men but the other was missing; parts of one were discovered mixed up in parts of the car on the top of a tree about 50 yards away.” (December 28, 1915) “One 4.2 landed on Lee-Warner’s (9th. Bty) dugout and burst inside. He was buried and his legs were badly crushed and he was suffering very badly from shell-shock and when he was taken away was talking absolute gibberish.

“That is the seventh time he has been hit during the war.” (July 31, 1916) “Once I saw three men coming down with a wounded man whose only garment was a bandage on his head.

“He appeared to be raving mad as he was struggling vigorously.” (October 1, 1916) This is interspersed with long periods of boredom, as on August 4, 1915: “Then I read till tea and then messed about and wrote my diary feeling extremely bored.”

Finally on November 11, 1918: “THE WAR IS WON. At 10am I heard that the Armistice had been signed by Germany and was coming into force at 11am.

“Told the Battery at Stables. Great enthusiasm.”

By the end of the war, Gordon had been awarded the Military Cross and been mentioned in despatches.

He continued to serve with the military after the Great War and was made a CBE during the Second World War.

He retired to the Audland family home in Ackenthwaite in 1951, where he fulfiled voluntary public duties, and died in 1976 at the age of 79.

In Sir Christopher Audland’s autobiography ‘Right Place, Right Time’, he remembers his father as ‘quiet, calm, reserved, modest, thoughtful, considerate, generous and utterly dependable’.

“He had a strong Christian commitment and a stern sense of duty,” wrote Sir Christopher.

“He was someone whom everybody loved to know: after his death, my mother took comfort from the multitude of tributes received from many local people.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article