Kendal historian Arthur R. Nicholls recounts how stealing was dealt with in by the authorities in the past.

The Commandment, "Thou shalt not steal" was taken seriously by both rich and poor alike in Kendal from earliest days and stealing was often prompted by extreme need.

In 1717 a labourer stole a sack of oatmeal from a shop in Kirkland. He was sentenced to be stripped to the waist and whipped along the road to the Cauld Stone in the centre of town.

In 1720 Joseph Addison was placed in the stocks for an hour for petty thieving and then tied to the whipping post where his back was lashed until the blood ran down.

Women were also punished harshly. Margaret Fuller stole a cartload of peats worth only twopence. She was first sent to prison and then carted to Blind Beck, naked to the waist, with the word "THIEF" on a board on her back.

In 1822 John Watson was transported for seven years for stealing a letter from the Post Office and, in 1832, a man was sentenced to death for stealing tobacco.

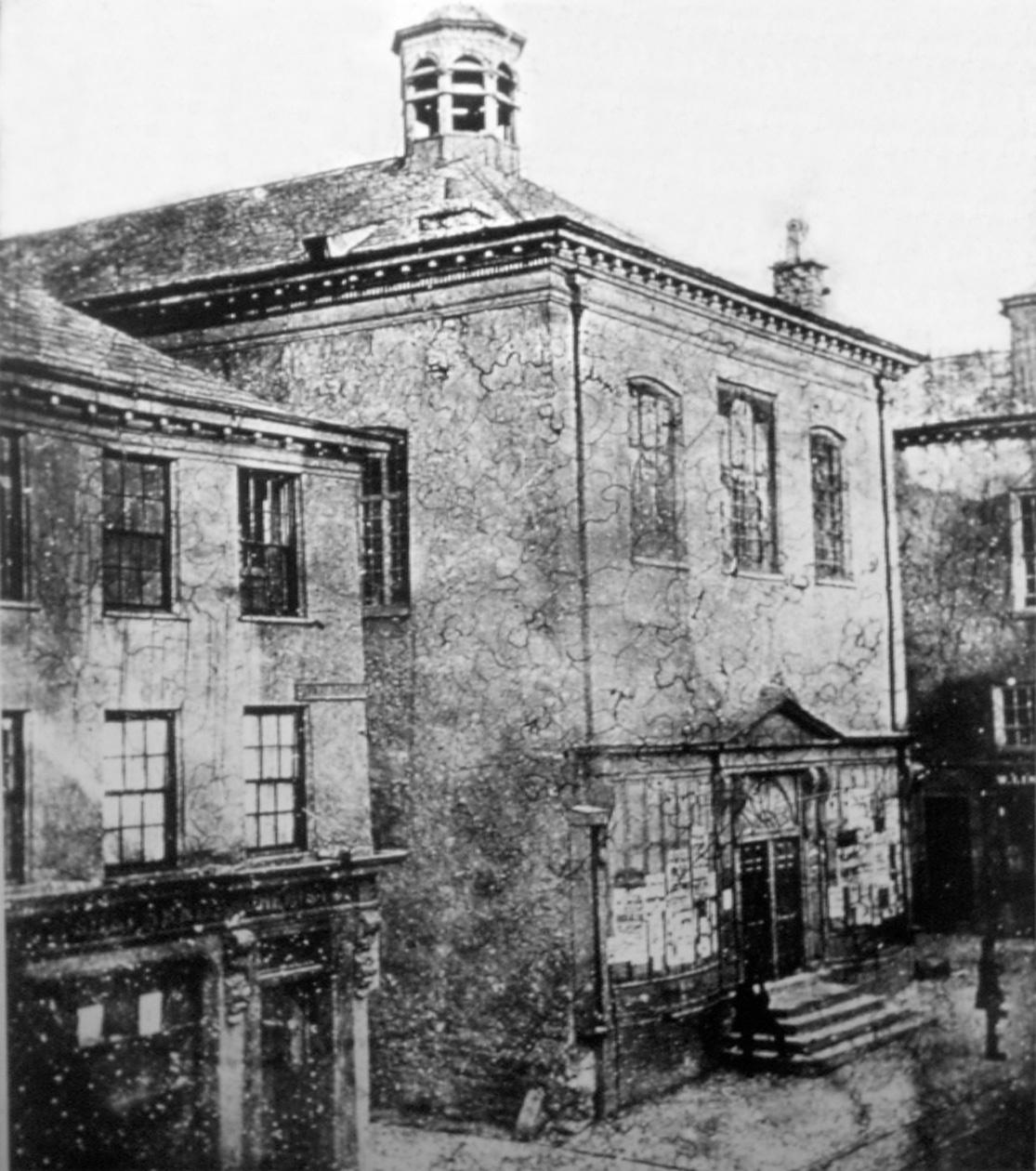

Some offenders spent time in the dungeon, otherwise known as the Court Loft or Black Hole, which was under the St George's Chapel in Market Place, beside the Moot Hall where the Borough Court was held.

Offenders were often discharged from the town with a warning never to come back again.

A case of unpremeditated pilfering on 1859 led to a chain of events that raised a furore in the town.

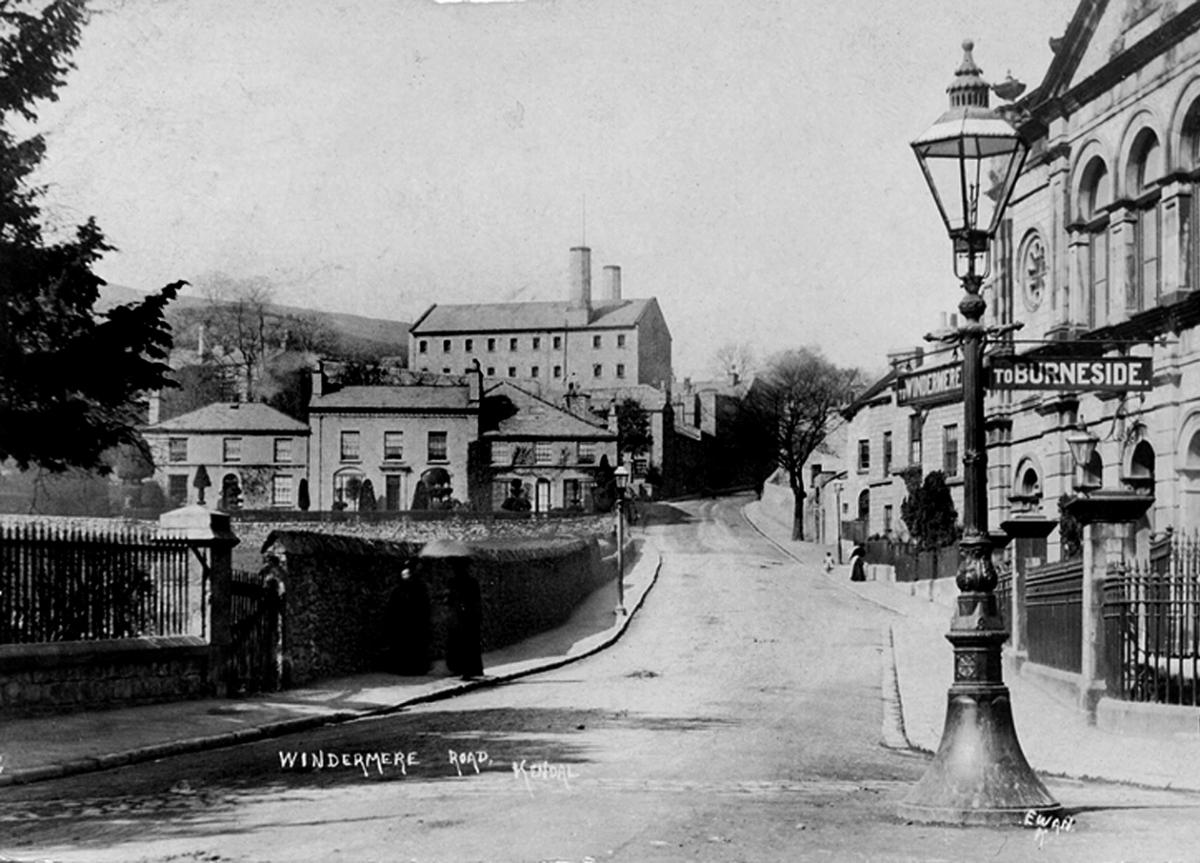

Thirteen-year-old Hannah Rushworth saw an unattended bag on the platform of Kendal railway station and took it away.

It belonged to the Rev Henry Lowther, who was visiting the town and spending an hour or two in the Commercial Hotel. Returning to the station he found his bag missing and reported it.

Hannah's father was honest and hardworking and noticed that she was spending more money than she should and after much questioning and denial she admitted the theft.

It seemed to be a rather minor offence but all echelons of society abhorred theft in their own way.

Hannah's uncle tried to put matters right, speaking to his employer, John Jowitt Wilson, and giving him the bag to trace the owner and return it. However, the railway company prosecuted Hannah.

Wilson pleaded for the case to be dropped in view of her young age, asking that it be dealt with under the Juvenile Offenders Act but it was sent to the Appleby Assizes, where she was sentenced to two weeks in the House of Correction, and five years domestic service in Milnthorpe Workhouse.

Feeling ran high among the working classes at the harshness of the sentence and looked on Wilson as their champion for their efforts to achieve justice for Hannah raising 70 guineas to present him with a testimonial on parchment and a silver coffee service and salver for his efforts.

Thanking them, he said that Hannah's father had done all he could to restore the stolen property and repair the wrong but the law had no mercy.

He did his best to obtain the Magistrate's discretion to avoid a public trial and was severely attacked for his pains.

Justice had been done, but at what a price. It was certainly rough justice in those days.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here