'RETURN TO PEACE'. Roger Bingham sketches local activities during the festive season of 1918-1919.

The Armistice which brought to an end the First World War in November 1918 meant that the ensuing festive season would be celebrated in peace.

Even so, along with the Christmas cards, arrived news of continuing casualties with reports of deaths from wounds, sustained earlier in Europe and from combats and disease resulting from conflicts in Ireland, Russia and the Middle East.

At home, in the tail end of the influenza epidemic, 20 deaths occurred locally, during Christmas week.

An upsurge of tuberculosis also caused fatalities, including Mrs Knowles and her daughter form Milnthorpe, who died within four days of each other.

Both scourges, possibly hastened by war-time deprivation, were, however, mitigated in hark backs to Victorian 'seasonal benevolences'.

At Kendal, 100 blankets from Mrs Bindloss' gift were bestowed on the aged poor; calico and flannel were dole out at Dent, while in Burton Mrs Shorland-Ball 'arrayed the school girls in new red cloaks'.

Warm clothing was especially welcome because, due to a coal strike, it was hard to keep the home fires burning.

Even so, at Ingleton, the nearest pit village to Westmorland, the colliery band played to crowds in the Square and again at Kirkby Lonsdale on New Year's Eve.

Nearby, one of the first Women's Institutes at Kearstwick organised a whist drive and dance.

At Milnthorpe the traditional New Year's 'Shouters', accompanied by a violin and a banjo, regaled every house after midnight.

Up at Windermere though, the 'streets were too sloppy for first footers, there was praise for the diligence on the road men in removing snow from the side walks'.

Also, in a New Year's hunt, the Ullswater fox hounds killed two of their prey actually in the lake, while at Kendal, three boys who had emulated their betters by killing three domestic pets in a 'cat hunt', were fined 10 shillings each.

In some places like Heversham, children's parties were postponed on 'account of the flu' but generally the usual celebrations went ahead.

At Kendal's Howard Home Orphanage, the children were awakened by a gramophone playing 'Christian's Awake' before they emptied their stockings and pillow cases'.

Among much old time cheerfulness there were signs of 'a promising period of change'.

Some envisaged reforms were not totally welcomed. Kendal councillors grumbled that bathrooms were an 'unnecessary luxury' in the promised 'homes fit for heroes' and farmers objected to the raising of the school leaving age to 14.

Best of all, 'our lads' came home. Contradicting official propaganda, released Prisoner of War, Albert Gill from Endmoor declared 'I have nothing to say against my treatment' but, like other POWs, he acknowledged that Red Cross food parcels had 'helped him keep going'.

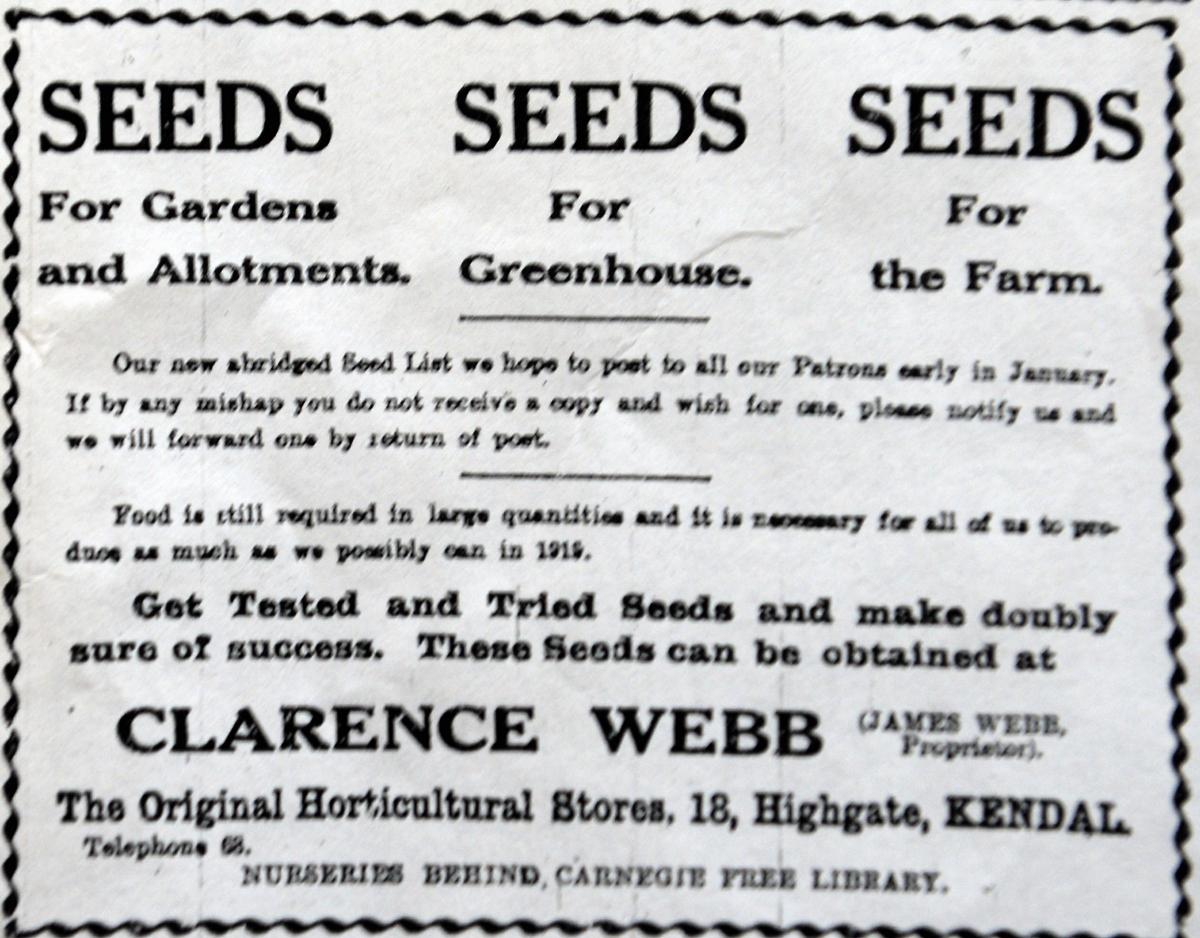

Unlike after the Second World War, there were immediate moves to end food shortages. Thornburgh's Butchers requested 'fat pigs wanted - porkers of any size'.

Some luxuries were also available. Atkinson & Griffin advertised 'Ford's Touring Cars at £250' while Johnson and Court Jewellers offered 'superior hooped diamond rings at £8:8' to cope with a flurry of engagements which had happily heralded the return of peace.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here