‘Bores and Quicksands’ – Prompted by a recent report of the successful rescue of people caught out on Morecambe Bay, Roger Bingham recollects the dangers associated with ‘Our Bay’.

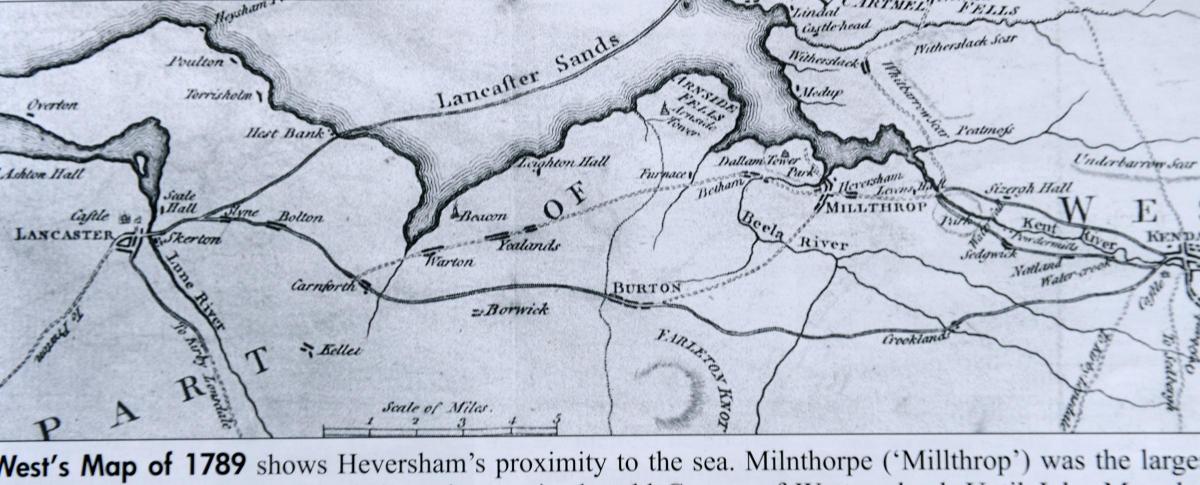

MORECAMBE Bay is the biggest bite in the Irish Sea coast of Cumbria. From Arnside round to Aldingham the Bay brings the seaside right into South Lakeland.

But alongside its maritime delights dangers have always lurked. As recently as 2004 more than 20 Chinese ‘cockle pickers’ were drowned, in what was one of the Bay’s most ghastly tragedies.

Before the railway and motor ages, many travellers who, having failed to heed the warning that ‘he who does not have a fast mount sacrifices his horse to the king’, were drowned while crossing ‘over the sands’.

Thus, a plaque in Beetham Church commemorates an over-risky winter traveller ‘Jonathan Bottomley, a clothier of Halifax, who was lost on our Sands Dec. 31st 1792’.

In 1815 a young ‘gentleman’, Thomas Barker of Cartmel, was swept away by the bore and in 1847 an older man drowned in the tide. He 'was on the tramp and his companions did not know his name or where he came from’.

Ironically, the main riddle of our sands is that they are not sand at all but are composed of alluvial mud, which forms speedily lethal quicksands.

Often disguised by a seemingly friable veneer they are most prevalent in the Kent estuary on Milnthorpe Sands, running from Blackstone Point up to Sandside, and in the Keer estuary, which drains into Warton Sands near Silverdale and Carnforth.

As early as 1723, John Lucas, School ‘Maister’ of Warton, illustrated the proverb that ‘the Kent and Keer have parted many a good man and his Mere (mare)’ by recording fatalities in what he called ‘Quicksand Poos’.

Three men including a relation ‘who was supposed to understand the sands were swallowed and they and their horses suffocated at once’.

So engulfing was the mud that it might be years before the bay gave up its dead. Once when a channel bank collapsed ‘a body was observed of a man on horseback with his right hand lifted up, his whip in it as if to strike the horse’.

Also, Lucas recalled, a ‘buck was found standing upon his feet with his horns on his head, five yards deep’.

Later, in June 1842, at Halforth, near Heversham, on the furthest tidal reaches of the bay, the ’sands’ disgorged part of a woman’s skeleton, which turned out to ‘be from the wife of the man Smith, a nailer’.

She had drowned near Ulverston the previous Christmas. ‘Part of the head and one arm was missing but she was recognised by her boots’.

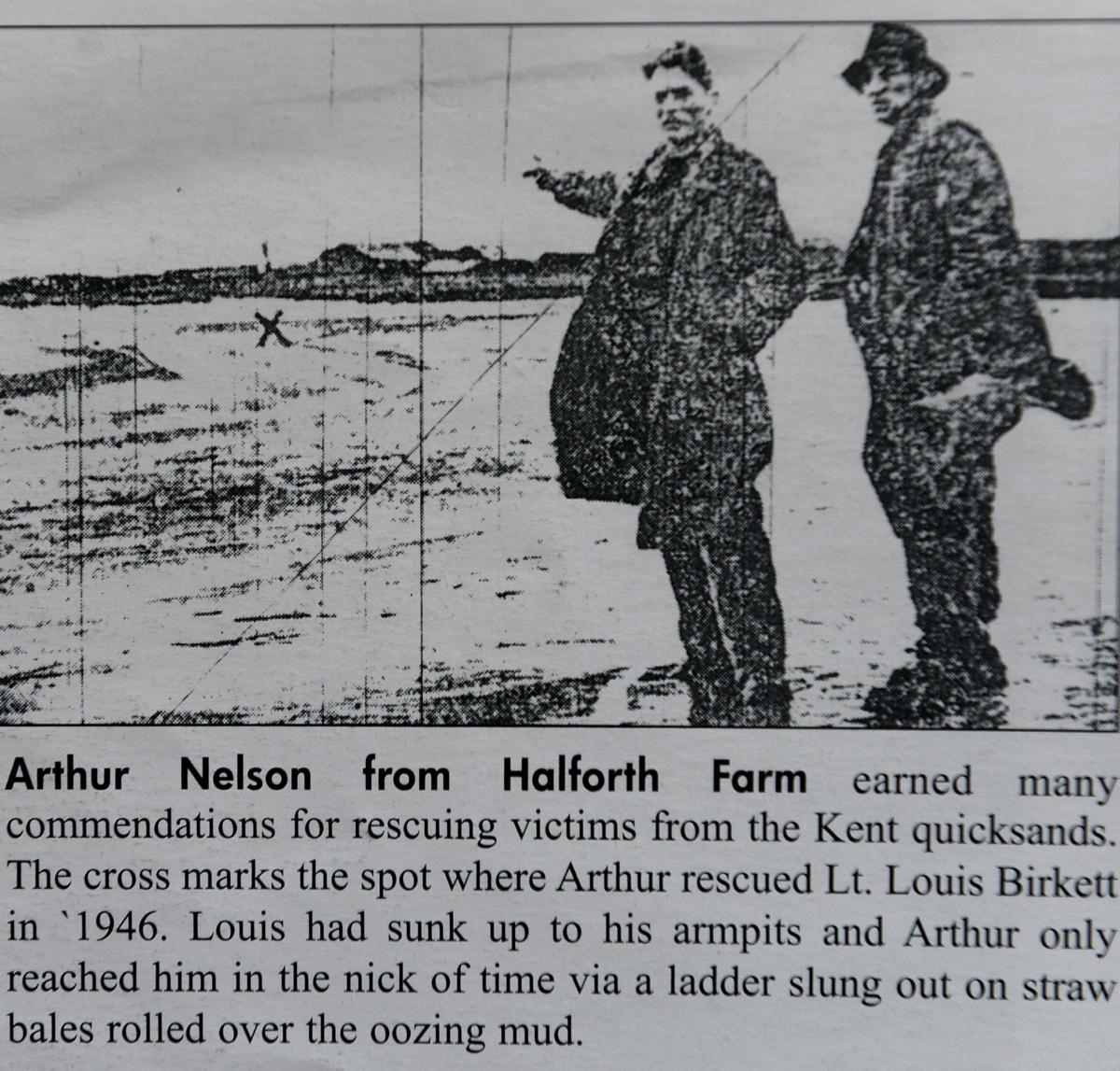

A hundred years on, in the 1940s, when, in good weather, the Kent estuary became ‘Westmorland’s Little Blackpool’, the farmer from Halforth, Arthur Nelson, won several gallantry awards for rescuing folk caught on – or almost under – the sands.

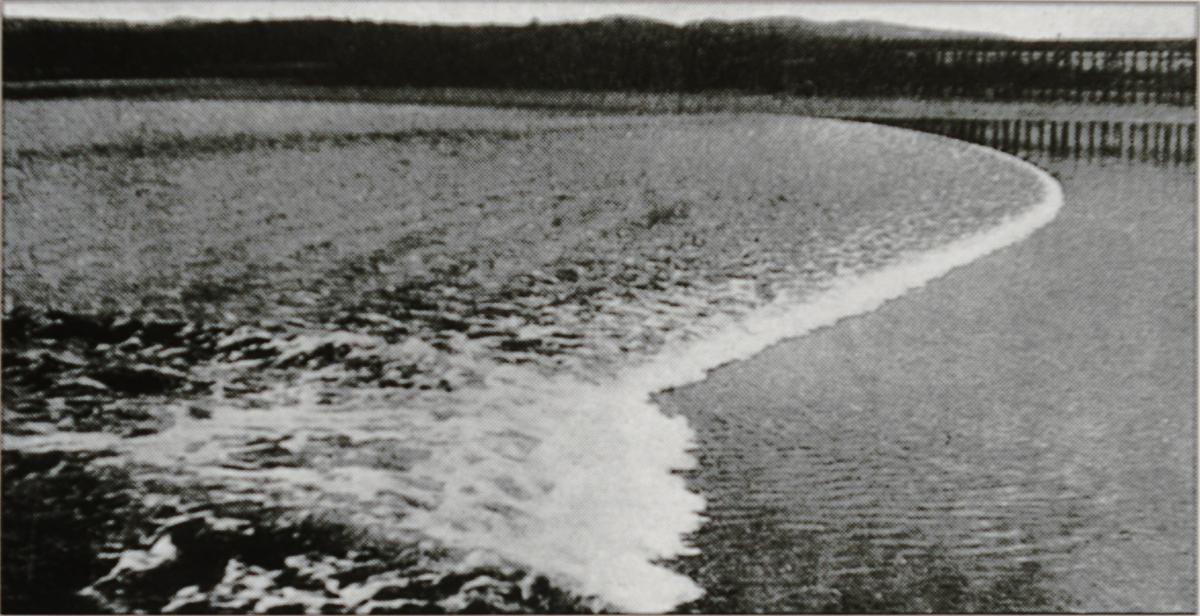

Nowadays though fewer folk flock to South Lakeland’s shores, the hazards remain, of which the most insidious are the bores and the quicksands.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel