Historian Roger Bingham sketches the celebrations 'When the Canal came to Westmorland'.

JUNE 18, 1819, was hailed, at the time, as a 'most glorious day' when the northern reaches of the Lancaster to Kendal canal were officially opened on the fourth anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo.

The great event had been a long time coming.

Way back in 1729 Kendal corporation had petitioned the government to improve the road between the town and the port of Milnthorpe, through which the town's vital coal supply was imported.

In 1717 James Brindley, the designer of England's first coal-canal from Worsley to Manchester, drew up plans for a canal from the Wigan coalfield at Westhoughton to Kendal.

But another 20 years went by before James Rennie was appointed as the engineer and the share holders set about raising the necessary capital of £414,000.

By 1797 the canal had crossed the River Lune via Lancaster Aqueduct, (the tallest such structure at the time), to reach the edge of Westmorland at Tewitfield.

Here the need for five ascending locks halted the route's progress so seriously that, in 1805, an alternative tramway was proposed to run through Burton to Kendal.

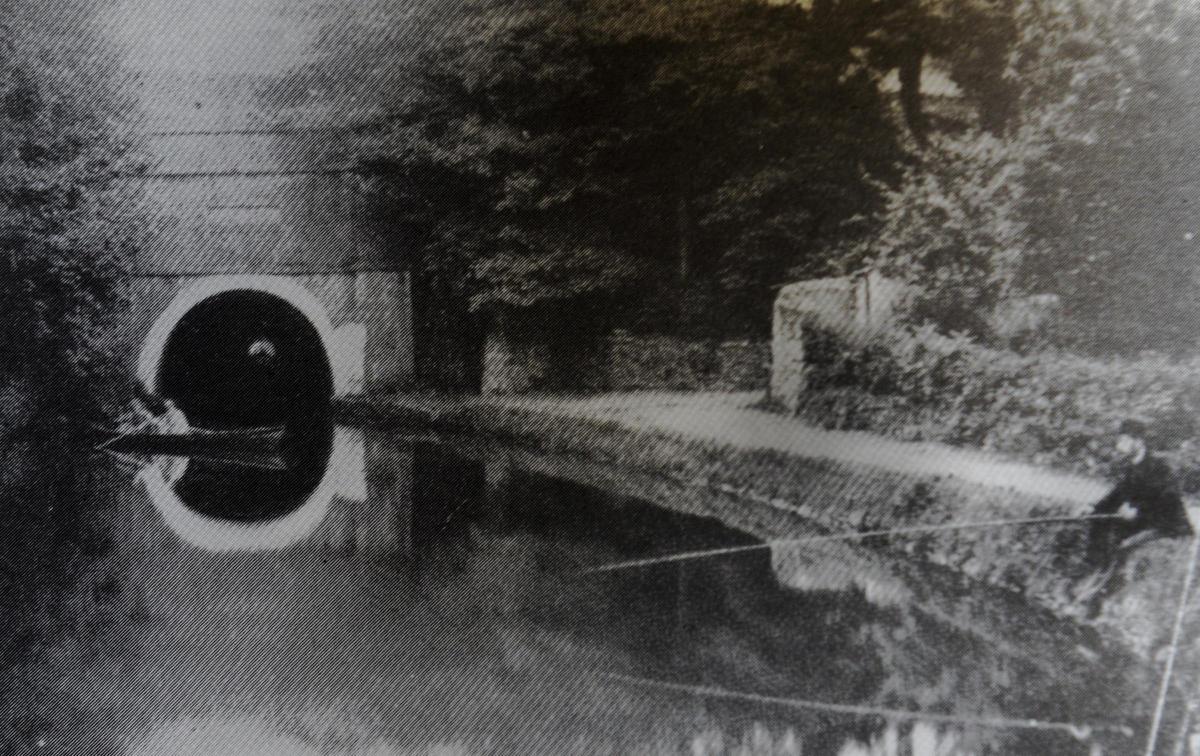

When the work resumed in 1807 it took a decade before the canal reservoir at Killington and a tunnel at Hincaster were created.

Two more years then passed before numerous bridges, which included 13 on a three mile stretch between Burton and Holme, were finished.

A brief disruption occurred in 1818 when, according to one of the first crime reports in the recently-founded The Westmorland Gazette, a man called Douglas absconded with two months wages of the canal navvies, who got 8s per week.

Fortunately, though hundreds of workers were camped at Netherfield, Crooklands and Farleton, no disturbance resulted.

A trial trawl occurred on Wednesday, April 14, when a boat loaded with paving stones came up from the south end to the new basin at The Aynam, Kendal.

For the grand opening, a procession of 16 boats left Kendal at 9am for a rendezvous at Crooklands, with a similarly be-flagged flotilla headed by the Mayor of Lancaster.

There were several floating bands, and behind the civic vessels trailed a convoy of respectable inhabitants and a large party of ladies, followed up by five boats laden with coal, one of timber and three commercial barges belonging to the Widow Welch and Sons.

The Gazette enthused, "the whole scene was one not only of novelty, but of extraordinary grandeur: the landscape presented a most beautiful and rich variety or rural objects, every bridge and elevated spot was crowded with spectators whose number was beyond calculation who occasionally evinced their feelings with loud huzzas".

Eventually the bulk of the cortege banqueted in Kendal Town Hall and also a the King's Arms at Stricklandgate, where 15 separate toasts, headed by those to the ailing King, George III, and to the Prince Regent, were drunk.

Other joyous and no doubt bucolic celebrations were strung out along the canal route.

Even so, the Gazette concluded, "we are happy to say that not a single accident of a serious consequence occurred during the day; though several individuals were thrown into the canal, they did not sustain any other injury than an involuntary immersion in the cold bath".

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here