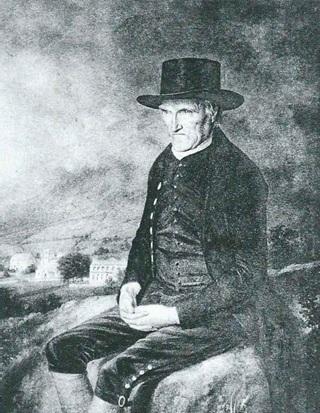

Kent Brooks describes the life of John Dawson of Garsdale: mathematician, physician and philospher

EARLIER times are not known for social mobility but there are many instances (not only Dick Wittington) where people of humble origins rose far in society.

One example was John Dawson, of Garsdale.

Dawson had an astonishing career by any standards.

His family (William and Mary) farmed at Raygill in Upper Garsdale. He was born in 1734, the youngest of two sons, attending the school in Garsdale.

While his elder brother was earmarked for comfortable job as a minor civil servant, John was destined to be a farmer like his father.

John soon left Garsdale School claiming “severe treatment” and studied alone using his brother’s books.

He worked full time on the farm but was able to earn some money by knitting while attending the sheep and this he used on books bought on his rare visits to Sedbergh.

He studied in the evenings by the light from the peat fire. This did not prevent him, while sitting shepherding on a large boulder high on the fell, from coming up with a mathematical formula of a highly original and complex nature relating to the conic sections.

In his early 20s he became apprenticed to a surgeon in Lancaster, learning new skills, which allowed him to be a surgeon and apothecary in Sedbergh. Thereby he saved £100 and set off on foot for Edinburgh to attend lectures in the university, although his funding soon ran out.

After some time practising again he was able to amass £300 and travel to London, obtaining a medical diploma. Here he became known for his astonishing insights into mathematics, but he found London far too expensive and returned to Sedbergh to run his medical practice.

He subsequently used his talents to show that Professor Mathew Stuart of Edinburgh University was wrong in his method of calculating the distance from the earth to the sun and that this could be done by detailed observations of the orbit of Jupiter. Captain Cook’s voyage to Tahiti in 1768 vindicated Dawson’s conclusions.

Dawson was able to give up regular medical practice in 1788 and survive by giving tuition.

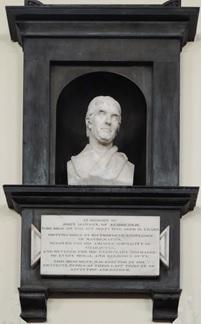

He was famous as a very fine teacher and many of his pupils attained high ranks in the academic world.

He was a man of modest disposition and enjoyed walking his native fells or solving mathematical questions while on horseback visiting patients. He continued as a teacher almost to his death in 1820.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here