Kendal Celebrates Victoria

To mark the 200th anniversary of the birth of Queen Victoria Roger Bingham sketches the varying attitudes in Kendal to our second longest reigning monarch.

ON MAY 29, 1819 The Westmorland Gazette reported that, at Kensington Palace, on May 24, ‘HRH The duchess of Kent was safely delivered of a Princess. The Prime Minister (Lord Liverpool), the cabinet and the Duke of Wellington were in (discreet?) attendance’.

Even so, the arrival of the sixth in line to the throne was not big news. But 18 years, and the deaths of three kings later, the Mayor proclaimed the accession of ‘HM Queen Alexandrina Victoria’, just a month after the Corporation had marked her coming of age with a municipal ball.

The next year, her first name having been dropped, Kendal’s celebrations for the coronation of Queen Victoria included five triumphal arches, splendid processions, a tea for 3,000 children, while ‘further sustenance for 870 poor people was dispensed from a special soup kitchen’.

Then, for a while, civic largess dwindled. In 1840, only church services greeted the wedding of Victoria and Albert while ‘HM’s natal day’ was sarcastically reported as being ‘marked with high éclat, namely the hoisting of a dirty, patched Union Jack on the Town Hall’.

Similarly, the birth of the Prince of Wales in 1841 was meagrely acclaimed ‘by a tattered flag’ while a brief reference at a public meeting was ‘in neither respectable nor meaningful terms’

Monarchical feelings warmed up in 1858 when a ball and tea parties welcomed the marriage of the Princess Royal to Prince Frederick of Prussia – who, within a year, became the parents of the First World War’s German Kaiser.

When, in December 1861, Prince Albert died all the town’s shops shut on the funeral day, although it was only two days before Christmas.

Queen Victoria never set foot in Westmorland. But some of her entourage may have done so, as according to legend, the Royal train, which twice annually steamed, at 25mph, through the county en route to Balmoral, would pause on Shap Fell for ‘the convenience’ – amongst the bracken – of the ladies-in-waiting’, whose carriages lacked the facilities of the Royal compartment.

Victoria, herself, was glimpsed just once, in 1851, when her train halted (but not for a comfort break) at Milnthorpe Station where onlookers were rewarded with a regal nod.

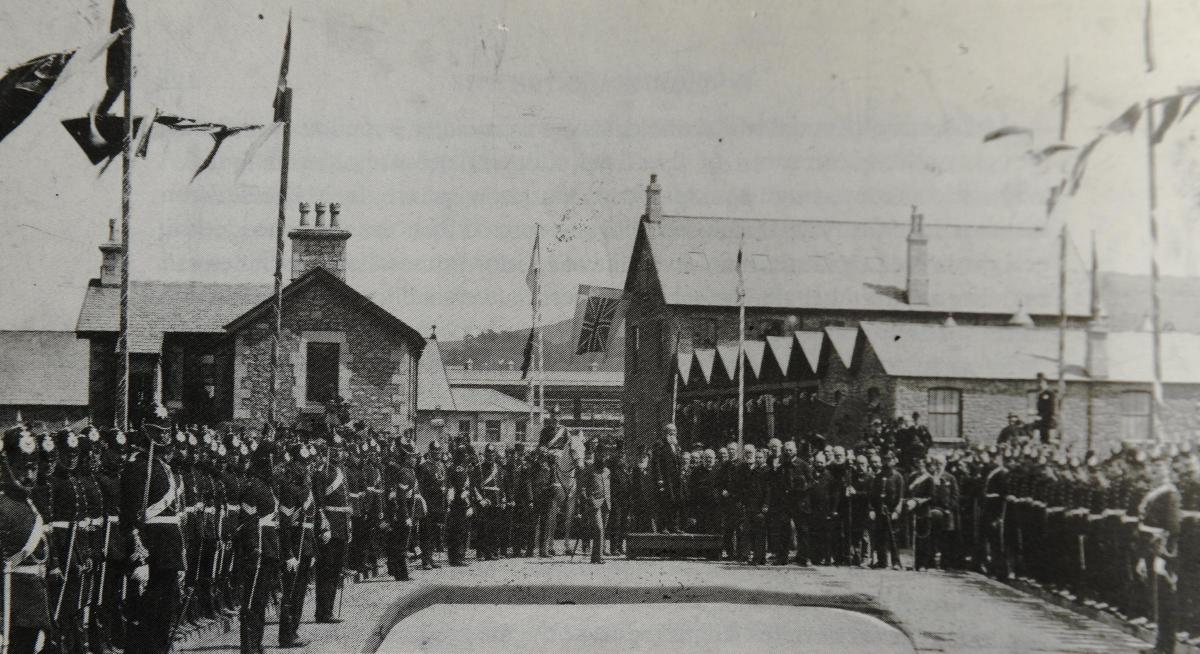

Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887, was permanently commemorated by The Royal Arms on the Market Hall in Kendal and by the, splendidly Victorian, ‘Victoria Bridge’ over the river Kent at Sandes Avenue.

Her Diamond Jubilee in 1897 was celebrated equally rapturously with sports, meals, parades and with a dodgy verse from Canon H.D. Rawnsley: “As long as Kings shall reign and Queens be nursing mothers, O God make fast the chains that binds us sisters brothers.”

When Victoria died, in 1901, loyalty to the crown was so widespread that an ‘old woman aged 68’ was crushed to death in the huge crowds which had turned out for the proclamation of Edward VII.

Yet, despite this ‘painful incident’, the National Anthem was sung with great fervour though, The Westmorland Gazette reported, many people failed to remember that the refrain was now “God Save The King” and not “The Queen”.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here