ON A nightly phone-in Nightline, presented and produced by Caz Graham, there were stories of real heartache, huge frustration and often complete fury at, and incomprehension of, the strategies and procedures that were being used to control the foot-and-mouth virus.

Here Caz gives a voice to what she experienced 20 years on, and how foot-and-mouth had some parallels with Covid-19.

I listened back to some of the radio archive from the time and there are parts of it that still, 20 years on, leave me to the verge of tears because it’s so raw.

Day in day out we were hearing from people who were struggling with the trauma of losing control of their lives and their businesses as well as the guilt and desperation of having to witness the slaughter and disposal of livestock they’d bred and nurtured and were responsible for looking after.

You could hear the strain and exhaustion in their voices, barely concealed emotion brimming to the surface as they struggled to keep their act together and not break down while they were speaking.

There’s always that little catch in the voice, the tremor, the silences that speak volumes.

And that’s what we’ve heard again so often throughout the Covid pandemic, A and E staff who’ve witnessed far too many deaths and family tragedies, often ones that seem needless, they talk to the tv cameras with red rims around their eyes, looking totally spent and incredulous at what they’re dealing with.

It would be crass to claim the 2001 FMD outbreak affected most people on anything like the scale of this covid pandemic – we’re talking about upwards of a hundred thousand people who are tragically no longer with us, that’s the population of Carlisle, and the grief and pain of all their family and friends. But there are definitely parallels.

Both FMD and Covid meant things we took for granted were suddenly forbidden. In 2001 going out on the fells, a stroll through the woods, a walk across the fields were all illegal.

The National Park put up big yellow posters threatening fines of up to £5000 for if you broke the rules, much like the fines and even threatened jail sentences used to make the public comply with lockdown restrictions now.

We all wondered what we could and couldn’t do. Was it OK to drive south of Shap or was it too risky?

Would you be frowned on by neighbours, even if you did scrub your car at the disinfectant station on the A6 and drive carefully over all the disinfectant mats on the road? We’re replaying that now on a much bigger scale.

And talking of disinfectant stations, there’s the language of disease and its prevention that suddenly jumps out of the textbooks and into everyday use: in foot and mouth we all became experts in bio-security, confirmed cases, Restriction of Movement orders and wondered scarily whether we were ‘clean’ or not. Here we are in Covid grappling with much the same.

The daily lists of figures are a reminder too. In 2001 we used to listen to the daily count of confirmed cases, whose farm was lost to the outbreak, whose cattle or sheep would be next for the pit or the pyres and we’d do the mental maths to see who else farmed nearby and would have to lose their stock too under the compulsory cull.

Those lists of numbers were very grim, but of course nothing like as sobering and upsetting as the ones we hear now each day about Covid.

But both sets of numbers share one characteristic; they’re so large they’re almost hard to take in.

The Lessons to be Learned Inquiry after the 2001 outbreak said at least 6.5 million animals had been slaughtered, possibly many more.

The global tally of people affected by coronavirus over the last year is equally hard to comprehend.

For me one of the most striking similarities between 2001’s FMD epidemic and today’s Covid pandemic is the way these two episodes made people feel.

The scale of events in both cases was overwhelming and again, in both cases, there’s been a strong sense that those who were supposed to be in charge and on top of the situation were always two steps behind, making questionable decisions and detached from the truth, the reality of what the epidemic and pandemic really meant.

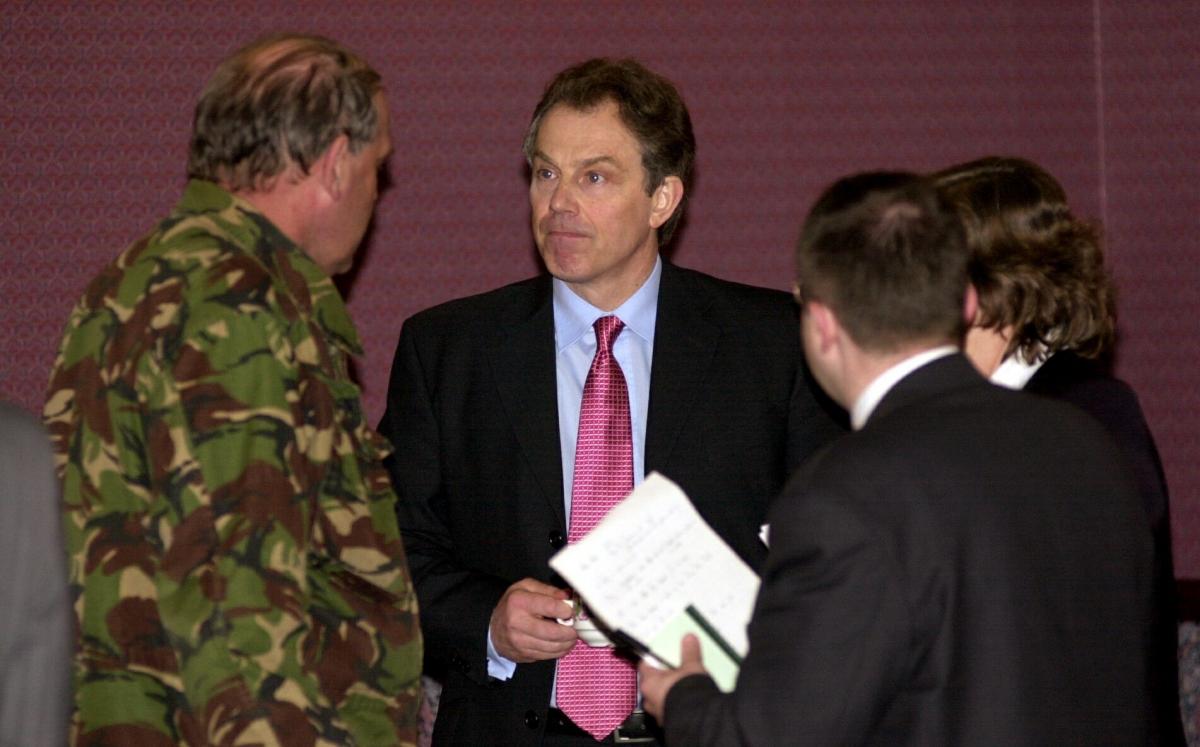

Too little too late. I remember when Tony Blair came to Borderway Mart In Carlisle, getting out my microphone and recording the furious sound of the crowd there to meet him, one snapshot from that morning: a farmer, I assume he was a farmer, evidently totally frustrated and irate, he’d lost all faith, all hope, in the people who were making the decisions, he was bellowing “get away back to London” his voice crackling with anger and dismay and incredulity that all of these suited and booted officials and the PM thought they could jet in for a few hours to sort out what was by then a disaster for farming, the rural economy and tourism in Cumbria.

I think seeing just how raw foot and mouth still is for those who lived through it even now 20 years on, should give us a good idea of the impact the covid pandemic is likely to have on the mental health of those who’ve been at the heart of this pandemic. The scars will be deep and take a very time to heal.

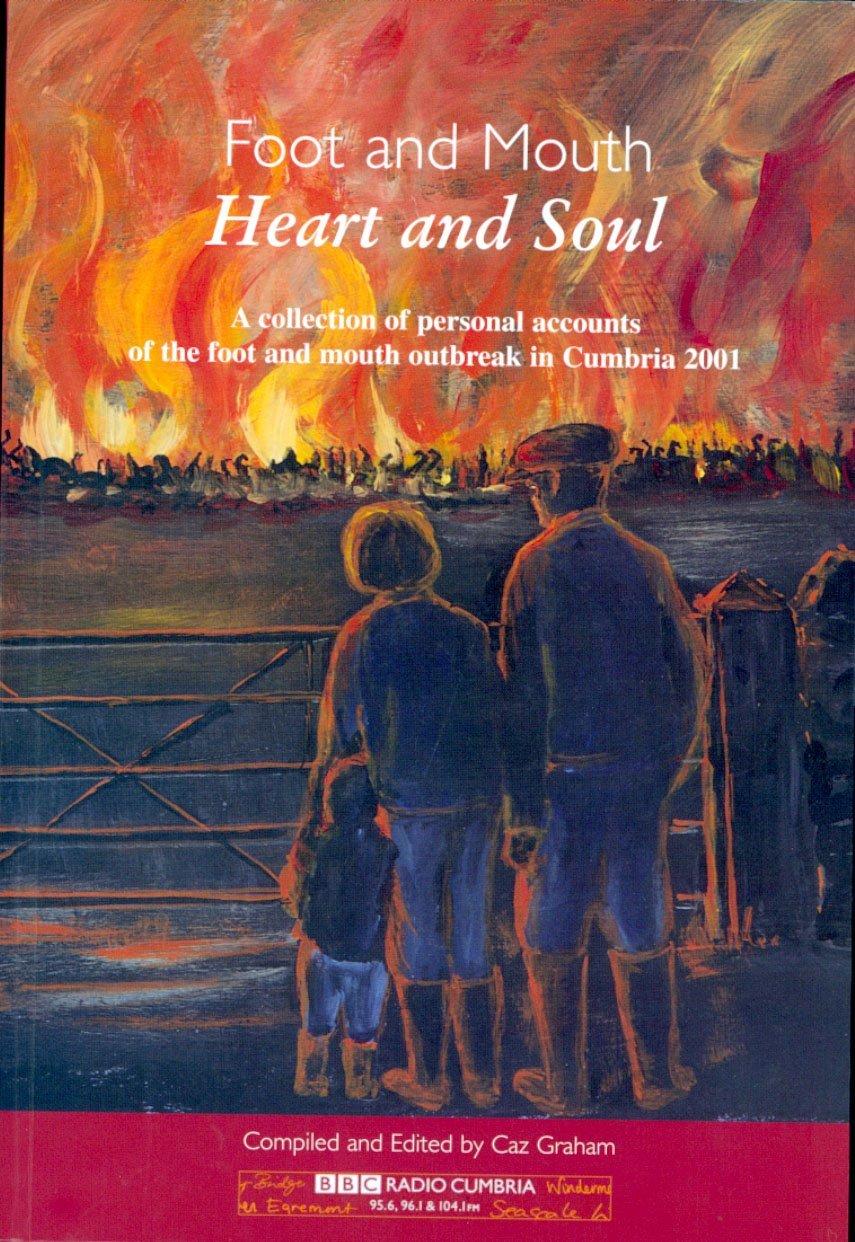

Caz compiled, edited and published a book Foot and Mouth - Heart and Soul, a 208 page collection of personal accounts, documentation and photographs of the foot and mouth outbreak in Cumbria in 2001.

Sixty copies of the book were purchased by the EU for members of its Temporary Committee of Inquiry into foot and mouth, it was used by members of the Anderson ‘Lessons to be Learned’ Inquiry, was launched by Greg Dyke, Director General of the BBC in December 2001, has sold 7000 copies and became widely acclaimed as a compelling social history of this traumatic episode.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here